Water scarcity has evolved beyond an environmental concern into a core macroeconomic, geopolitical theme with profound implications for growth, stability, and investment.

The scale of water deprivation is staggering. Today, more than 2.1 billion people lack access to safe drinking water, while nearly 500 million remain under constant water scarcity. About 10% of humanity—approximately 720 million individuals—already endures high or critical water stress. Projections warn that by 2050, three out of four people worldwide could face drought impacts.

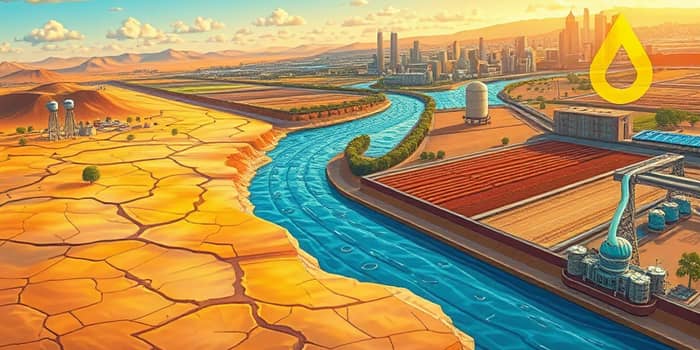

On the demand side, urbanization, population growth, rising incomes, and expanding food production are increasing water withdrawals. By 2030, global freshwater demand is projected to outstrip supply by roughly 40%, as erratic weather patterns disrupt traditional sources.

Economically, water scarcity poses a tangible drag on growth. The World Bank estimates up to a 6% GDP reduction in regions like the Middle East, Sahel, parts of Sub-Saharan Africa, and Asia by 2050. Modeling shows losses across agriculture, health, income, and property.

BIS research spanning 1990–2020 highlights how a one‐standard‐deviation rise in water scarcity affects economies:

At the household level, inadequate water and sanitation lead to roughly US$260 billion in lost opportunities annually. Time spent collecting water, especially by women, reduces labor participation. Achieving universal basic access could generate US$18.5 billion per year in economic benefits from avoided deaths, with each dollar invested returning about four dollars in productivity and healthcare savings.

Current extreme water stress plagues the Middle East, North Africa, the Sahel, Southern Europe, parts of North and Central America, India, China, and sections of South America, Africa, and Oceania. By 2080, climate projections paint a world strewn with regions facing extreme scarcity.

Agriculture, responsible for roughly 70% of global freshwater withdrawals, remains the largest consumer. One-quarter of irrigated cropland is already under high water risk, jeopardizing staples such as wheat, rice, and sugarcane.

Emerging research in Nature Communications reveals that physical scarcity (withdrawal-to-availability ratios) does not always correspond to economic impact. Some basins convert scarcity into trade advantages through price signals, becoming “virtual water” exporters. Others, such as the Indus and Lower Colorado, hover near an economic tipping point, where minor supply wobbles trigger major losses due to limited groundwater and alternatives.

This distinction underscores that water scarcity is an economic and market issue, enabling policy and investment interventions to reshape outcomes.

As water security declines, social grievances intensify, raising the specter of conflict over shared rivers and aquifers. Strategic assessments warn that shortages threaten food, energy, and political stability in highly exposed regions.

Scarcity can catalyze migration, heighten inequality, and fuel social unrest, as vulnerable populations lack resources to adapt. The interplay between water insecurity, food prices, energy costs, and employment magnifies these stresses.

Financial authorities are taking note. BIS suggests that central banks may soon incorporate water availability into macro-forecasting models, given its influence on inflation and growth. For investors, water risk is increasingly viewed as systemic ESG and credit risk, rivaling climate in its cross-sector implications.

Zurich Insurance labels water as “the invisible risk,” warning of far-reaching corporate repercussions. Companies face operational shutdowns, supply-chain disruptions, regulatory hurdles, and reputational damage as water stress intensifies.

Firms with unpriced water dependencies—for example, reliance on cheap groundwater—risk margin erosion as tariffs rise and stricter allocation rules emerge. Asset impairments loom when operations become uneconomic under scarcity scenarios. Investor scrutiny via ESG ratings now often includes basin-level water metrics.

The stakes are enormous. WWF values water and freshwater ecosystems at around US$58 trillion per year—about 60% of global GDP—highlighting the magnitude of assets at risk from over-extraction, pollution, and climate change.

Investor attention on water has surged. The “Currents of Capital 2025” report found that 96% of senior leaders plan to maintain or increase water-sector investments, with 40% ranking water opportunities as a top priority.

Yet funding falls short of need. UNCTAD reports a 40% drop in water and sanitation projects in early 2025, with virtually no new projects in Africa and a 97% decline in Latin America and the Caribbean. The global water infrastructure funding gap spans trillions of dollars, demanding innovative public–private partnerships, blended finance, green bonds, and scalable solutions.

As water scarcity reshapes economies, geopolitics, and corporate fortunes, investors who integrate robust water strategies will not only mitigate risk but also harness systemic risk and opportunity. Aligning capital with sustainable water management can unlock resilient growth, foster social stability, and preserve vital ecosystems for generations to come.

References